“The very survival of the nation will feel at stake. Sometime before the year 2025, America will pass through a great gate in history, commensurate with the American Revolution, Civil War, and twin emergencies of the Great Depression and World War II...The nation could be ruined, its democracy destroyed, and millions of people scattered or killed. Or America could enter a new golden age, triumphantly applying shared values to improve the human condition.”

Written on the cusp of the dot-com bubble, The Fourth Turning is an anachronism. Like The Sovereign Individual, it projects a future almost wholly unforeseeable during the go-go 1990s, where we wondered if were at The End of History. Twenty-five years later, the book reads like an uncanny prophecy for the turmoil of the new millennium.

The central thesis of the book is that history, rather than progressing linearly or chaotically, moves in rhythmic cycles. The concept of a “saeculum” dates to the Romans: a suggestion there was a rhythm to the “timing of great perils and Rome’s subsequent eras of renewal and innovation.” Over the course of eighty to one hundred years (the length of a human life), civilizations or groups go through similar cycles.

Using retrospective analyses of the past to project the future is perilous for several reasons. Chief among them is applying a deterministic quality to history, a complex adaptive system governed by human action. Moreover, once a phenomenon is identified, human behavior changes and shifts to accommodate new knowledge.

However, what I most enjoyed about this book is it offered a coherent narrative for the possibility of a better future in America. Most analyses extrapolate from the recent past: we hear dire warnings of impending disintegration due to polarization and technology stagnation. Others are Pollyanna-ish: Warren Buffett tells you to Never Bet Against America, but there’s little explanation why other than this is a bet that’s worked during his lifetime. This book offers a path for why this was to be expected and why we may come out better on the other side.

If the Soaring Twenties are at hand, how will we get there?

Call this an optimistic thought experiment.

Without a vision, the people perish.

Proverbs 29:18

The First Turning: The High

History begins with the victory over a crisis: an enemy tribe, plague, or internal strife. These are the moments where civilizations are reborn or disappear. Following the grand victory, there is an upbeat era of strengthening institutions, commercial prosperity, and a new civic order. Howe and Strauss emphasize the importance of generational roles in the First Turning:

A Nomad generation ascends to elderhood and leadership. Pragmatic and shrewd, this group wants very little to do with grand ideologies and wants to maintain the peace and security of the recent hard-won victory. George Washington and Queen Elizabeth I are archetypes of this generation. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s warnings over the military-industrial complex still resonates.

A Hero generation replaces Nomads in midlife institution-building roles. They are ambitious, confident of improving every sphere of public and private life. Thomas Jefferson and his peers were certain of victory in the Revolutionary War. After the victory, they managed the nation through “energy in government,” “order and harmony” in society, and “abundance” in commerce. The Greatest Generation won World War II, built the institutions that would take man to the moon, passed sweeping governmental reforms in The Great Society, and presided over a large growth in real wages.

An Artist generation are the helpers of Heroes, bringing the culture vitality and expertise. In previous Highs, these young adults were “regarded as the most educated and least adventuresome adults of their era.” Youths like John Quincy Adams were tasked with the goal of maintaining institutions while remaining “peaceable and silent.” As a percentage of the eligible pool, more Silent Generation men faced draft calls than Boomers, yet few protested. They were “plumbers of the national wealth machine,” maneuvering the system to accomplish their goals. Artists understand the inertia of the new institutions and try to win through compromise. Martin Luther King, Jr. built a movement through nonviolent protest and an appeal to conscience.

A Prophet generation is born during First Turnings. Nurtured by a prosperous and affluent society, this generation is urged to turn inward and develop deep spiritual lives. They are coddled and “sickened with advantages” as Jane Addams speaks of her generation. The Gilded Age’s kids grew up in a “long children’s picnic.” This is often a period of increased fertility as prospects have never looked higher. In our current saeculum, we know of this generation as the Boomers.

But the good times do not go on forever. As each generation grows up and reaches the next stage of life (Nomads reluctant retirement, Heroes elder statesmanship, Artists midlife, Prophets young adulthood), the strains begin to show as generations chafe against one another for responsibility and re-ordering of society.

The Second Turning: The Awakening

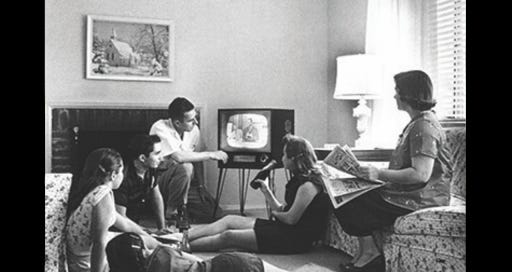

When John F. Kennedy was assassinated, the American economy was roaring. “Extrapolating from the last twenty years, top economists declared that Americans would soon...spend their lives consuming rather than producing.” Visions of the future looked like Tomorrowland and the Jetsons. When Kennedy urged America to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade, the Greatest Generation and their Silent helpers dutifully set to work, not questioning whether such a thing was possible or even a worthy goal.

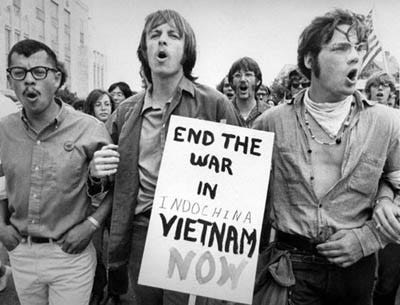

By the end of the 1960s and clinched by the stagflationary 1970s, America had irrevocably shifted from “Think Big” to “Small is Beautiful.” Environmentalism surged. Abundance was corrupting rather than aspirational. Unthinkable at the onset of the space race, some media outlets reminded people that “moon rockets diverted resources from poor people” when Armstrong landed on the moon. The Apollo program would ignominiously end a few years later.

What shifted?

Howe and Strauss argue that this is the natural second phase of the saeculum: the Awakening. Awakenings are religious in nature, either explicitly as in the Protestant Reformation of 1517 or the Great Awakening of the 1730s, or somewhat implicitly, like the Consciousness Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s.

It’s an era of “cultural upheaval and spiritual renewal” where the social discipline and order of the High are seen as oppressive, unfulfilling, and illegitimate. Memories of the last crisis have faded. The new generation of Prophets, often quite accurately, identifies injustices and inequalities that have been ignored and must now be resolved.

Each generation has now passed into a new stage of life.

The Hero generation is firmly established as the leaders of the civic order. At first hesitant and skeptical of the new values and ideas of the younger generation, they eventually reluctantly accede. Jefferson worried that the sacrifice of his generation would be “thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons.” The Greatest Generation found themselves “accused of moral outrages against nature, women, minorities, and the poor” and of wrecking the planet by their Boomer children. Eventually, they gave up arguing and ceded control of the culture and nation’s values to Boomers, settling for control of institutions and passing increasing entitlement programs. During the 1950s, elder benefits had fallen twenty percent behind wages; during the Awakening, what seniors were owed from the U.S. Government rose fifteen times faster than average wages.

The Artist generation is now in midlife. Having helped Heroes build many of the institutions that Prophets are questioning, Artists are caught in the middle of the squabble. The Silent Generation was the youngest- and most-married female generation in U.S. history, but also the first to begin prefixing themselves with “Ms.” as they grew older and questioned societal roles. Younger Silents were the graduate students who founded the dissent groups that Boomers would later radicalize. A Silent attorney convinced his father to lend the property for Woodstock. The ambivalence of the Silent Generation meant institution-building was now over as building powerful new things became difficult, subject to red tape, and a focus on harm prevention. Silents preoccupied themselves with setting up oversight committees and writing impact statements, exacerbating productivity stagnation.

The Prophet generation comes to young adulthood as “mystical militants whose mission [is] neither to build nor to improve institutions but rather purify them with righteous fire.” Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison vowed to “wake up a nation slumbering in the lap of moral death” at the height of the Transcendental Awakening. In the late 1960s, youth rage was channeled into moral and cultural issues rather than economic: Boomers still expected to find better jobs, make more money, and live in better houses than their parents on the other side of the revolution. The preference for cultural, rather than economic revolution, was no doubt exacerbated by the fact that many of the leading radicals were children of the elite, attending prestigious universities. The largest cause of youth revolt was the Vietnam War even though only one in sixteen male Boomers saw combat. Ten times as many committed draft law felonies as were killed in the war. New Age mysticism and Eastern inward-looking spirituality grew in popularity. The focus on morals and values was not limited to left-leaning Boomers: conservative Boomers would later form the Moral Majority and the heart of the American evangelical movement. The American economy began to be retooled as Boomers insisted on “meaningful careers,” ending America’s decades-long productivity surge.

A Nomad generation is born: independent children of an era where adults are preoccupied with religious crusades and moral awakening. They are cynical, growing up fast and competitive at an early age. Gilded youths like John D. Rockefeller were described as “commercial before they get out of their petticoats” and Tom Wolfe remarked about his own generation as being raised “without innocence, born old and stale and dull and empty.” The newfound animosity towards children during the mid-1960s evidenced itself through the new decline in fertility rate, as well as in the media. Smart-kid family sitcoms were replaced by demonic, savage, bratty, and unwanted children: Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, The Omen, Lord of the Flies, and Halloween. The Zero Population Growth movement declared children to be pollution. By the late 1970s, would-be mothers aborted one fetus in three. Instead of viewing adults as wise, children grew up thinking of their elders as incompetent or corrupt in an era of Vietnam, Watergate, and the gas lines of Jimmy Carter. The distinction of occupying America’s most poverty-prone age bracket skipped three generations from the previous Nomad generation (Wolfe’s Lost) to Generation X. The latchkey kids of Generation X were the first to grow up hearing a new message: America’s best days were over.

The transition to the Third Turning did not happen because the Awakening failed, but because it had won. The words of Eric Hoffer ring true here: “Every great cause begins as a movement, becomes a business, and eventually degenerates into a racket.” The anti-institutional shouts that “originated in the pot-lace dronings of Haight-Ashbury hippies could be heard in the free-market chatter of Wall Street brokers and Main Street merchants.”

The Third Turning: The Unraveling

During the Consciousness Revolution, Boomers had attacked the old civic order expecting to create either a utopia if they won or a dystopia if they lost. By the mid-1980s, they were now ascending into control of institutions, but unsure how to wield them and distrustful of the very concept. The cult of the individual was born. Each individual had their own niche group (divided by sex, race, religion, or even hobbies like gun ownership) with their own particular worldviews. There was no longer any such thing as “broad” or “normal” public opinion. Public discourse deteriorated as culture wars raged. Differences between Middle America and the coasts sharpened. Irving Kristol described this period as one where there was a “profound division over what kind of country we are, what kind of people we are, and what we mean by ‘The American Way of Life.’” Despite an extended economic boom, nearly three-quarters of adults believed America to be in a “moral and spiritual decline” in the mid-1990s. Hillary Clinton lamented a nationwide “tumor of the soul.” Events like the Oklahoma City bombing, O.J. Simpson trial, and whipsaw elections of 1992, 1994, and 1996 illustrated the nation’s turmoil and disquiet.

Howe and Strauss describe this period as one where “society clears away institutional detritus” and people pursue individual fulfillment. The Awakening is over and no crisis is on the horizon. Even Democrats like Bill Clinton declared the era of big government over. Free markets and free trade reign supreme. The term ‘laissez-faire’ itself was first popularized in the 1840s, another Unraveling period.

Artists replace Heroes in elderhood. As a generation that has always been flexible and hesitant to take strong stances, they try to find compromise in an era that shuns it. Decisive leaders are rare. The elders of the French and Indian Wars were remembered for their “endless doubts, scruples, uncertainties, and perplexities of the mind” while the peers of Zachary Taylor hoped for a harmonization of conflicting interests on the eve of the Civil War. The Silent Generation was the first to grow into its fifth decade without winning a major-party presidential nomination: when it did, Walter Mondale and Geraldine Ferraro carried just one state. Silents were demeaned as a generation with “flip-flopping inconsistency, pandering to special constituencies, and having questionable values.” They would have been the first to never produce a U.S. President without the 2020 election of Joe Biden, who barely qualifies as a Silent, having been born in 1942. Meanwhile during an era where they dominated governmental posts from 1977 to 1996, Congress didn’t balance the budget a single time and added “eight times as much to the national debt as all earlier American generations combined.” They tried to solve problems by getting people to talk to one another through corporate sensitivity seminars and instituted a foreign policy where “when Americans feel bad about some foreign situation they see on TV, U.S. troops go on on overseas missions with few clear goals other than adhering to multilateral agreements and keeping everybody from getting hurt.”

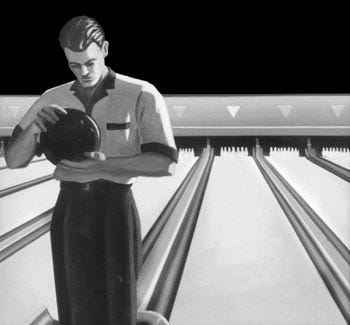

Prophets ascend to midlife, reshaping institutions from the inside out. The Puritans of John Winthrop demanded his followers to “submit to authority which is set over you,” their original “law of love transformed into a love of law.” The Missionary generation of the 1920s passed women’s suffrage and Prohibition. Boomer evangelicals started new megachurches while others dabbled in New Age spirituality. Al Gore accused opponents of a “jihad against the environment” and academics enforced political correctness and “inappropriately directed laughter.” Demographer William Dunn described Bill Clinton as the stereotypical Boomer: “self-indulgent and...convinced that he and his generation are smarter than everyone else.” Boomer politics had its roots in the Awakening: values, not economics, divided America and Vietnam remained a cultural touchstone. As they destroy old notions of teamwork and fraternal association by “bowling alone,” midlife Boomers hypocritically defend monogamy, family values, and thrift that other generations do not easily associate with the hippies of the 1960s.

Nomads become young adults, individualistic with no collective mission. In the 1650s, Josiah Coale described these youths as a “wicked and perverse generation.” The fighters of the French and Indian Wars were notorious for drinking, gambling, and crime. A century later, Nomad men rushed to the West Coast in search of gold. In the 1980s, Generation X were described as “mindless, soulless, and dumb” and an “army of Bart Simpsons.” Nirvana captured the mood of a generation when Kurt Cobain sang “Oh well, whatever, never mind.” Movies and tv shows depicted young adults as noncommittal, sex-obsessed, alienated, and violent from Clerks to Sex and the City to Dazed and Confused and American Psycho. Real median income for young-adult males fell by nearly thirty percent from 1973 to 1992, a larger drop than the entire nation experienced during the Great Depression. After growing up hearing that the best days were over, they reached the labor market just as America started a deep decline. Over a decade before popular Gen X journalist Malcolm Gladwell wrote Outliers, Howe and Strauss described a generation viewing “the world as run by lottery markets in which a person either lands the one big win or goes nowhere...being rich or poor has less to do with virtue than with timing, salesmanship, and luck.” They also suffered deeply from the laws passed by Silents and the Greatest Generation. Nearly every entitlement policy passed during the Unraveling era transferred money from youth to elder: during the same period where youth wages dropped precipitously, senior incomes rose by twenty-six percent.

A Hero generation is born. They are nurtured and urged to be obedient achievers. In the 1750s, when young men like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were growing up, “irresponsible parents became the nation’s scapegoat.” Progressive-era adults cleaned up the child’s world and passed child labor laws. In the 1980s, movies about demon children like Children of the Corn started flopping, replaced by Raising Arizona and Three Men and a Baby. A decade later, Millennial kids were heavenly and inspirational like in The Piano and Angels in the Outfield. America’s new view towards its children was once again reflected in Hollywood. Mario Cuomo called the 1990s “the Decade of the Child.” Boomer parents were the epitome of the “Do As I Say, Not As I Did” generation: family values, drug-prevention assemblies, and abstinence programs dominated the airwaves and schools. A protected generation, Millennials grew up feeling safe, wanted, and adored, a stark contrast to the Nomad children of the Awakening.

This is where the book gets most interesting. Written in 1997, it’s still in the late stages of the Unraveling. What happens next is Howe and Strauss’ projection for the future: the Fourth Turning, a multi-decade crisis that will rock the country and set the stage for either a new civic order or dissolution.

Thus far, we’ve mostly just reviewed the book’s thesis as it sets the stage for what comes next. I plan on fleshing out an analysis of the crisis as well as vision for the future in the next newsletter.

Stay tuned.

Apologies for the long delays in writing. I got busy with the holidays, but have set a goal of writing twice a month this year. Hope you all had a great Christmas and New Year. I’m looking forward to an awesome 2021.

Nutrition Tidbit of the Week

No tidbit this week, just eat steak and ignore government guidelines.

Book or Podcast of the Week

My favorite new podcast is Conservative Curious hosted by Jessica Dang and Anirudh Pai. Hosting heterodox thinkers, they have some of the most original conversations I’ve heard recently. Ani has a great episode on Venture Stories, writes an awesome newsletter, and was the person who endorsed The Fourth Turning. Happy to call him a friend and fellow Founding Member at Praxis (DM me for details if you’d like to join or have questions.)

Highly recommend checking all his content out.

See you in two weeks.