Compounding Competitive Advantage, Part II: Scale Economies Shared

Why AI agent companies may look more like Amazon than B2B SaaS

In Part I, I wrote about the core competitive advantages that can be unlocked in supply, demand, and scale. I would again generally emphasize that for very early-stage startups, thinking about moats is generally not as important as extreme focus, rapid shipping cadence, and customer-centricity.

I mentioned that Part II would cover some possible models AI-native companies could pursue like Aggregators, Scale Economies Shared, and Ecosystem Entrenchment. However, I’ve realized that there’s currently only one company (OpenAI) that has a shot at the Aggregator model and Ben Thompson has covered it well. I will likely still cover Ecosystem Entrenchment at some point (the lessons of Oracle and Salesforce continue to be underrated by most founders other than people like John Collison!)

This article will focus on Scale Economies Shared, current frameworks around AI services/agents, and how to potentially build in the new world.

Scale Economies Shared

Scale Economies Shared is the idea that rather than immediately profiting from the productivity and efficiency gains of scale, you give those gains back to customers with lower prices or better service, creating a virtuous cycle where increased growth drives further efficiency and deepens your moat.Nick Sleep is a legendary investor whose annual shareholder letters are often held up alongside Buffett as the must-reads for any aspiring investor. There are many insights around concentration, contrarianism, psychology management, etc. in these letters, but we’re going to focus on the business model that is one of his core insights and was responsible in part for his extraordinary outperformance: scale economies shared.

Nick defines scale efficiencies/economies shared with the following as he lays out the investment case for Costco in 2004 (up ~30x today):

“Most companies pursue scale efficiencies, but few share them. It’s the sharing that makes the model so powerful. But the center of the model is a paradox: the company grows through giving back. We often ask companies what they would do with windfall profits, and most spend it on something or other, or return the cash to shareholders. Almost no one replies give it back to customers - how would that go down with Wall Street?”

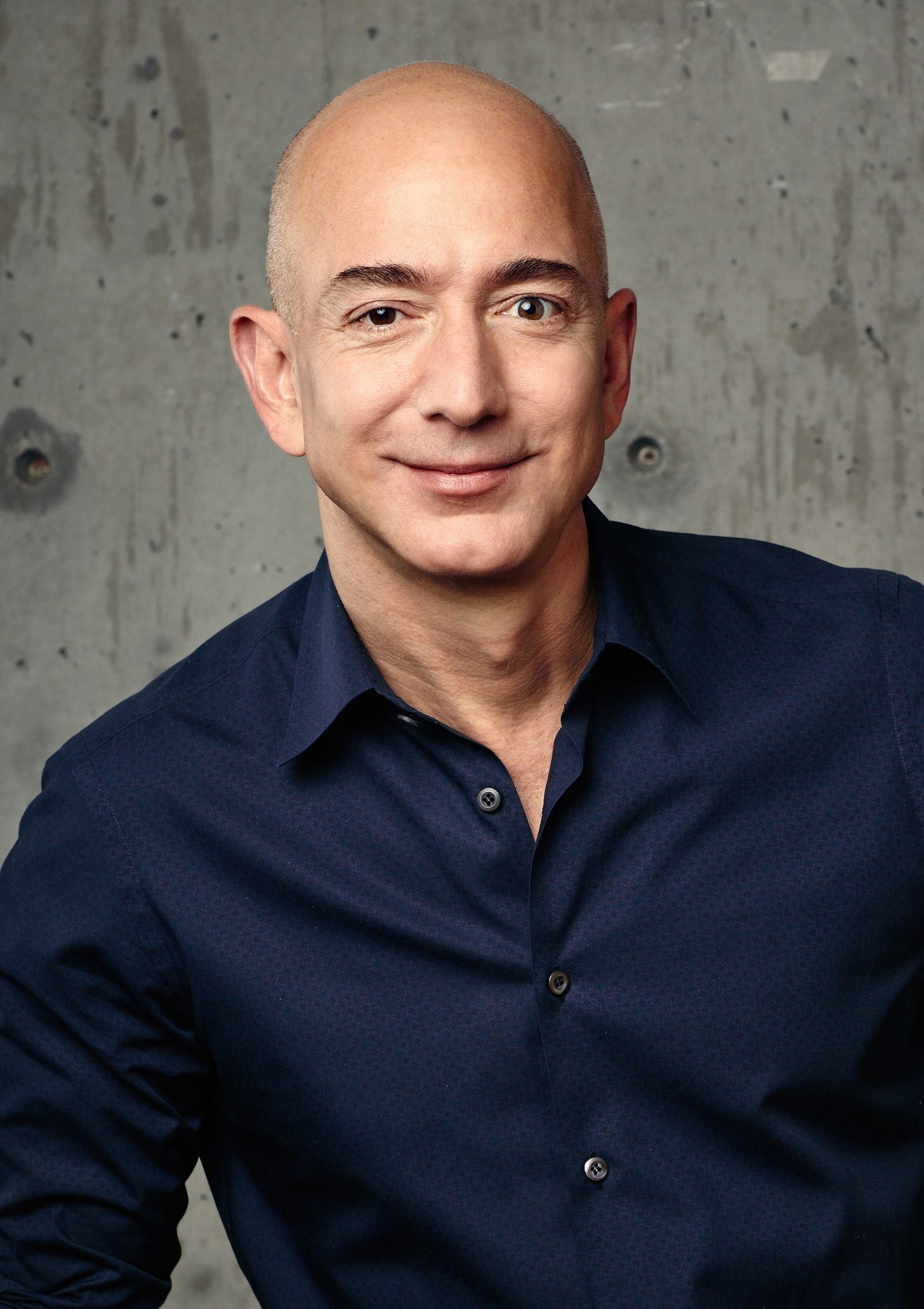

Scale economies shared leads to a widening moat as he discusses in the Amazon investment case in 2006 (up >100x today):

“If he [Jeff Bezos] shares the efficiency benefits that come with growth with his customers, he turns size, frequently an anchor on business performance, into an asset. In other words, the moat surrounding the firm deepens as the firm grows.”

Bezos is the king of applying the scale economies shared model: he was exceedingly customer-centric, focused on long-term value creation, allowing “growth to beget growth,” and created a widening moat that was very difficult to compete with for new entrants and competitors. His 2005 shareholder letter explains the beauty - and difficulty of implementing - of SES than anything else I’ve read:

“As our shareholders know, we have made a decision to continuously and significantly lower prices for customers year after year as our efficiency and scale make it possible. This is an example of a very important decision that cannot be made in a math-based way. In fact, when we lower prices, we go against the math that we can do, which always says that the smart move is to raise prices. We have significant data related to price elasticity. With fair accuracy, we can predict that a price reduction of a certain percentage will result in an increase in units sold of a certain percentage. With rare exceptions, the volume increase in the short term is never enough to pay for the price decrease. However, our quantitative understanding of elasticity is short-term. We can estimate what a price reduction will do this week and this quarter. But we cannot numerically estimate the effect that consistently lowering prices will have on our business over five years or ten years or more. Our judgment is that relentlessly returning efficiency improvements and scale economies to customers in the form of lower prices creates a virtuous cycle that leads over the long term to a much larger dollar amount of free cash flow, and thereby to a much more valuable Amazon.com.”

In Part 1 we saw that there were three core places you can build moats around: supply, demand, and scale. SES is the combination of scale with customer captivity on the demand side. Now that we understand what scale economies shared means as a business model, let’s examine current frameworks around AI agents and services companies.

Current Frameworks around AI Services/Agents

The prevailing AI‑services or agents playbook says something like:

Sell the work, not software: AI agents can replace human labor and complete the full JTBD rather than enhance a human. AI companies “selling the work, not software” can start underwriting to a large fraction of TAMs of the price of human labor in that market rather than the price of software.

AI services companies will be more scalable and significantly higher margin than conventional services companies, creating the opportunity for VC outcomes in traditionally non-fundable spaces.

However, there’s are some interesting counters to the current VC consensus that point out why this might not be true: 1) race-to-the-bottom pricing and 2) customers will pay agent rates, not human rates.

Jared Sleeper from Avenir points out that outcome-based pricing has significant friction and there may also be a race to the bottom on pricing and margin if outcome costs and AI costs drop. A high “value-based price” may not be sustainable over time.1

Nikhil Namburi from Two Sigma also makes a great point in “Don’t Sell Work, Give It Away” that “customers won’t pay ‘x% of human costs in 7 years. They’ll pay the prevailing rates of AI agents, which will be orders of magnitude cheaper than current human rate.’”

My current belief is essentially a resolution of these two competing POVs:

Companies will be able to “sell the work, not software”and build “AI-services companies.” However, they should not expect to capture even 10% of current labor market spend on the labor-replacement. There will be immense price pressure on AI-services and agents: they will not have significantly higher margins than traditional services and certainly not the ballyhooed margins of SaaS.

Many of these markets will still be big and worth going after, but founders are going to have change their mindset and build companies differently. The thinking should be something like the following:

Get big FAST and focus on the core concepts of scale economies shared, customer-centricity, and passing savings back to customers rather than trying to build a high-margin SaaS business. Throw out the frameworks and playbooks of the last decade and look to the same long-term thinking that Bezos and Costco and others used to build their businesses and instantiate that in your culture from Day 1. Let’s expand on these ideas.

Scale Economies Shared for AI Companies

Focus on market share and cost reduction

Don’t fight the race to the bottom on pricing for agents, lean into it: giving it away at cost and monetize some other way or with a small “every day low price” margin like Costco’s fabled 14%. Focus exclusively on market share and delighting the customer.

Here are two examples off the top of my head, but I think there are many ways to do this depending on the business you’re running:

Customer support: a CX agent that undercuts human cost by 80% today, and then automatically lowers its price another 20% when inference drops, driving adoption and forcing incumbents to follow

Accounting service: a bookkeeping AI agent that proactively drops its per‑invoice fee from $2 → $1.50 → $1.00 as volume scales, locking in SMBs.

As the cost of inference and building software falls, start to automatically expand features or data allowances for existing customers rather than raising fees. Focus on delivering superior service quality, better integration into customer workflows, and harness unique industry-specific insights harnessed through customer obsession. Here are some other ideas that may or may not work, but are indicative of trying to institute this process as top-of-mind for your team:

Automated Price Cuts: Tie per‑transaction pricing to your marginal cost curve, and constantly advertise your “everyday low pricing” for agents.

Usage‑Based Add‑Ons: When inference costs fall X%, automatically give customers Y% more capacity or features.

“SES Metrics” Dashboard: Report monthly on cost‐per‑unit, price‐per‑unit, customer NPS, growth rate to your leadership team and show how each cost saving is returned to user.

Flywheel Experiments: Run A/B tests on 0% vs. 5% vs. 10% price cuts and measure lift in adoption and retention.

Scale economies shared is not simply about low prices, but building a virtuous flywheel with customers: lower prices attract more customers → increasing scale of customers is used to invest and reinvest in better infrastructure and products for customers → which then drives further cost reduction and increased customer satisfaction, and so on.

Culture of SES Companies

One of the core lessons from Costco and Bezos is that if you are relentlessly obsessed with passing savings back to your customers, that culture needs to be instilled from Day 1. Sleep described Costco as a company as “it is indicative of the paranoia with which the company is run that costs are measured in basis points.”

Building a customer-obsessed, frugal culture is a marked departure from the luxurious, perks-obsessed startup culture of the past decade. In Big Tech, most employees are optimizing for value-extraction from the company rather than value creation. Founders who are looking to implement this model will have to find ways to reward and incentivize this behavior internally and live it out themselves. Throughout The Everything Store, there are anecdotes about the various things Bezos would do to continually reemphasize frugality:

“With door-desks and minimal subsidies for employee parking, he was constantly reinforcing the value of frugality. A coffee stand on the first floor of the Pac Med building handed out loyalty cards so a customer could get a free drink after his or her purchase. Bezos, by now a multimillionaire, often made a deliberate show of getting his card punched or handing his free-drink credit to a colleague waiting in line next to him.”

While this might read as borderline cheesy or ridiculous, it instilled a culture of discipline that persists to this day. Of course, it’s important for employees to “know the why”: passing those savings and all others back to customers even as the company scales.

Gross margins in the early days may be significantly lower than traditional SaaS or even your competitors in the early days, which will perhaps leading unsophisticated investors to write you off.2 However, my hunch is that pursuing the scale economies shared model leads to more cumulative value creation.

The goal isn’t cost leadership as the end itself, but to build an operational model and culture that reinvests cost savings and efficiency gains into more growth and customer value: a long-run self-reinforcing compounding advantage.

Conclusion

AI agent and services companies face an inevitable race to the bottom on pricing and margin. Competition will massively increase as the cost of building new software drops to near-zero. The biggest barrier to entry and competitive advantage a company can build is through scale and customer delight.

Rather than borrow from the SaaS playbooks and company-building lessons of the past decade, companies should instead learn from Amazon, Costco, and other companies that mastered the “scale economies shared” model of Nick Sleep. Instilling a culture that obsesses over customers, operates frugally, grows big fast, passes efficiencies back to customers, and resists the urge to “profiteer” needs to happen from the earliest days of company building. Founders who pursue this model will have to continually emphasize and reward the inputs to that culture in a world that often doesn’t understand or value it. Amazon, Costco, and many other companies were misunderstood or mis-advised for a long time.3

You’ll be fighting an uphill battle for many years, as Bezos and others also did. But if you’re right, like he was, you’ll build a compounding business that lasts for decades and delights your customers.

If you’re building an AI‑services or agents startup today, don’t ask “How do I build like the SaaS darlings of the 2010s?” Ask instead “How do I make my cost curve fall fastest, gift every basis‑point of gain back to users, and use that delight to build a moat that deepens with scale?” If you nail it, you’ll unlock one of the deepest, self-reinforcing moats in business, a virtuous “perpetual motion machine”4 of customer delight powered through scale economies shared.

Pursuing this kind of business model for AI companies is significantly counter-intuitive to the mainstream narrative so I would love to hear thoughts and feedback. And if you’re a founder who thinks this an interesting way to build a generational company and wants to pursue it, please e-mail me pratyush [at] susaventures [dot] com

An example he shared with me over e-mail:

“For example, a CX company charging $1/resolution for customer support requests could easily find itself in a position where the "market price" for a resolution falls to 60 cents over time. Perhaps right now they're running at a 50% gross margin due to compute costs- but those compute costs fall to zero as AI advances.

Simplistically, you might expect that to expand their gross margins- but it also leaves them quite overpriced relative to the market and it will be a challenge to adjust.”

There’s a great detail in the recent profile of Neil Mehta where some of the “best VCs in the world” showed up to the Coupang Series B and wrote the company off because of its 8% gross margins. The founder was exclusively focused on maximizing value for customers, knowing that through scale and cost efficiencies, these margins would improve and expand to Amazon-style margins of 30%. A similar story may happen for AI companies who start off lower margin but can eventually expand through additional revenue streams, add-ons, more workflow capture, etc.

Example of bad advice companies often get: all companies in economic downturns should focus on profitability. Sometimes that might be the right time to go for the jugular on market share.

Nick Sleep’s framing.

Great essay and I appreciate that someone is willing to challenge the orthodoxy of SaaS and subscriptions (which are a customer financing tools and not business models!) and explore native business models.

You might like this - and the whole series of essays here:

https://getlightswitch.substack.com/p/most-consumer-software-doesnt-fail

Hello there,

Huge Respect for your work!

New here. No huge reader base Yet.

But the work has waited long to be spoken.

Its truths have roots older than this platform.

My Sub-stack Purpose

To seed, build, and nurture timeless, intangible human capitals — such as resilience, trust, truth, evolution, fulfilment, quality, peace, patience, discipline, relationships and conviction — in order to elevate human judgment, deepen relationships, and restore sacred trusteeship and stewardship of long-term firm value across generations.

A refreshing take on our business world and capitalism.

A reflection on why today’s capital architectures—PE, VC, Hedge funds, SPAC, Alt funds, Rollups—mostly fail to build and nuture what time can trust.

“Built to Be Left.”

A quiet anatomy of extraction, abandonment, and the collapse of stewardship.

"Principal-Agent Risk is not a flaw in the system.

It is the system’s operating principle”

Experience first. Return if it speaks to you.

- The Silent Treasury

https://tinyurl.com/48m97w5e