Early-stage startups do not have real moats.

“You’re either protected by barriers to entry or you’re not. If there are no barriers to entry, then many strategic concerns can be ignored. A company does not have to worry about interacting with identifiable competitors…[there’s too many to deal with, it’s just about operational efficiency.]” - Bruce Greenwald

Operational efficiency for later-stage companies means something very different than for early-stage startups. For early-stage startups, “operational efficiency” is likely some combination of:

Extreme focus on finding PMF1

Rapid shipping cadence

Creativity and invention combined with some level of customer discovery

Worrying about competitors or strategizing around maintaining a structural competitive advantage versus other players makes little sense when the game itself is in a state of flux and dynamic change.

The only moat, if any, that a startup can have in the early days may be uncertainty: the market is too too small, the tech nascent, the business model unproven, etc.

“Uncertainty can be seen everywhere in the startup process: in the people, in the technology, in the product, and in the market…uncertainty is not just a nuisance startup founders can’t avoid, it is an integral part of what allows startups to be successful. Startups that aim to create value can’t have a moat when they begin, uncertainty is what protects them from competition until a proper moat can be built. Uncertainty becomes their moat.” - Jerry Neumann

That uncertainty advantage seems to have been reduced as of late as startups and tech have become mainstream. While there are still companies that can build moats early due to operating in a small niche, it’s rare to find those operating in these verticals that have the possibility of exploding into something larger. Meanwhile, nearly every semi-obvious idea has dozens of competitors. VCs are happy to post a new market map with plausible whitespace every week. In the AI world, where access to the best technology is either an API call or open-source implementation away, most startups are drowning in a sea of me-too challengers.

Despite all this, eventually some startups will reach escape velocity and develop competitive advantages that compound over time. Even if it’s nearly impossible to have one in the early days, I do believe it’s useful for founders to start thinking about this topic early on. The genetics of the company are often baked at origin and have influence long after many of the people who were there at the start are still around. Amazon’s culture of ruthless efficiency and cost-cutting lingers to this day and helps power their compounding competitive advantage of “Scale Economies Shared.”2

After surveying some of the literature around competitive advantage, I tend to like Bruce Greenwald’s breakdown where he buckets competitive advantage into three core areas of supply, demand, and scale.3 I’ve further broken them down into parts based on other readings like Helmer, Neumann, etc.

Supply Advantage

Cornered Resources

People

Technology (sometimes patented)

Exclusive ownership over resources/supplies

Process Power

Demand Advantage

Brand/Habit

Switching costs

Search costs

Scale

High fixed cost advantage

Network effects

Part Two will cover the three of the strongest examples of compounding competitive advantage models that a company can have, particularly focused on where opportunity may lie for AI-native companies: Aggregators (h/t Stratechery), Scale Economies Shared, and Ecosystem Entrenchment.

Supply

According to Greenwald, a supply advantage is a “strict cost advantage that allows a company to produce or deliver its products or services more cheaply than competitors.”

These are usually in the form of cornered resources or process power.

Cornered Resources

People

This is probably the one that most startups or investors will cite as the competitive advantage for their startup: the founders and early team. The problem with this one is that founder excellence is not unusual when compared to TRUE peers and it’s thus hard to make this a persistent source of advantage versus equal competitors. A founder or CEO being excellent only matters versus their relevant competitors, not the population at large. This is why VCs often talk about “spiky” founders: being in the top 0.1% of the population at large is simply table stakes.

Consider all the code-gen/AI SWE competitors out there right now: Cursor, Codeium, Cognition, Factory, Magic, etc. Aren’t all of these teams excellent? Do any of them have a real people advantage versus the other? It’s hard to give a clear answer to that. Even at the frontier labs, we’ve seen dozens of key employees and researchers switch teams and seen corresponding level of output.

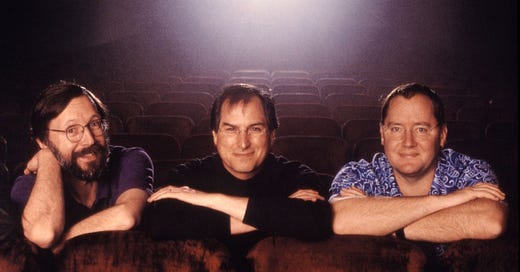

Individual people are a big part of the early slope and rise of a company, but they rarely translate into structural competitive advantage unless the person or team is a true 1-of-1 (eg: Elon Musk, Palmer Luckey, the Pixar trio of Jobs, Catmull, and Lasseter, etc.)

Technology

A great source of defensible competitive advantage is a patent that actually holds up in court. Drug patents are excellent for this. Tech patents rarely are. The quickest way to have a VC question your business knowledge is to say that a patent is going to help protect your SaaS company from competitors.

Obsessing over “proprietary technology” was actually one of the big misses investors made made when they critiqued GPT wrappers in early 2023 and every startup was urged to build its own “proprietary” models. The issue for some of the early wrapper companies was not that they didn’t have a proprietary model, but they had low switching costs to substitute suppliers and weren’t entrenched in the workflow of their users. A couple of years later, most startups have ceded model production to the foundation model providers and the “wrapper” critique doesn’t have the same derogatory sting it once did. In fact, everyone’s excited about value capture at the “application layer”…aka, wrappers.

Proprietary technology can sometimes a source of competitive advantage, but it’s difficult to keep the secrets from leaking out over time. A famous example of this historically was the knowledge transfer of how to build sophisticated cotton mills from the UK to America. Samuel Slater, a young apprentice in the UK, memorized the details and took the design to the USA, much to the chagrin of British cotton producers. The potential for knowledge ‘theft’ or distillation4 is nearly impossible to stop at any reasonable organization size. Being located in a hub like San Francisco amplifies this. As people switch companies, date one another, chat at parties, knowledge spreads.

Technology competitive advantages usually work best when paired with another source of competitive advantage (ie: scale, customer captivity, etc.)

Process Power

The iconic example of this competitive advantage is the Toyota Production System. Helmer points out that “process power” is not merely operational excellence: it’s the complex and opaque power of process improvement and tacit knowledge that can’t easily be communicated to others. Explicit knowledge like “how to build a cotton mill” or “how to build a transformer-based LLM” can easily be transferred between organizations. Comparatively, true process power lives internally in compounding company know-how and long-term hysteresis that is difficult to replicate.

This usually only works in industries with complicated processes like manufacturing where “learning and experience are major source of experience are a major source of cost reduction. Companies that are continually diligent can move down these learning curves ahead of their rivals and maintain a cost advantage for periods longer than most patents afford.”5

Consider a proposal to have TSMC “help” Intel or other American manufacturers build chip foundries in the US in a joint venture. While sounding great on paper, it is very unlikely that the American foundry would replicate TSMC’s output or quality due to being much further behind on the learning curve, without the tacit knowledge and internal company process power developed over decades. As an analog, GM saw this in car manufacturing when it attempted to bring over the Toyota Production System to its own lines, even though they had Toyota's help!

For most startups, this will not be a significant opportunity for future competitive advantage.

Resources/Supply

This is also less relevant for most technology startups, but exclusive access over oil fields, diamond mines, or airport location, etc. can be a source of differential profits and a defendable competitive advantage. We’ll leave this part short because it’s rarely applicable to venture-backed technology companies.

Now that we’ve covered the core supply advantages, let’s move onto the demand side of the equation.

Demand

There are two major types of advantages companies can build on the demand side: customer captivity through branding (particularly habitual purchases) or high switching/search costs.

Branding (Habit)

Branding is probably one of the most commonly cited moats that a company can have, but it’s usually overstated if it comes to teasing that out as a reason for persistent and differential profits compared to competitors. A key underlying point is brand “recognition” is not the same as brand "power.”

Strong brands also must be built over time, where customers come to expect a certain level of quality, experience, etc.

“[A brand is the] distribution of likely outcomes that you can expect from any company or person. Brand is forming an expectation, then creating a perceived probability of achieving it.” - Brent Beshore

Brands can lose their value in many ways: expansion creating brand dilution, changing customer preferences, counterfeiting, etc. One of my long-running shticks is that Lululemon has excessively diluted their brand to the point of becoming suburban dad-wear that it will lose market share amongst high-value, aspirational customers and cede ability for abnormal profits to Alo, Vuori, etc. The quest for expansion often has disastrous consequences: a story outlined in Competition Demystified highlights how Coors went from a highly profitable, successful regional brand with real cachet that celebrities like Paul Newman would go to extreme lengths to buy, to a diluted, marginally profitable national brand during the 1970s-1980s.

Habitual purchases offer a strong opportunity for building a durable brand. Greenwald writes, “Habit leads to customer captivity when frequent purchases of the same brand establish an allegiance that is as difficult to understand as it is to undermine…habit succeeds in holding customers captive when purchases are frequent and virtually automatic.” Subscriptions work well for a reason as a way of extracting loyalty and captivity from customers.

One of the most insightful things you can do when looking at technology companies is frequency of usage. A famous example is Mamoon Hamid seeing the usage of Figma users and leading the Series B at $115m post when it had ~$500k of ARR. He saw that Figma was becoming a habit that its users wouldn’t easily give up and would definitely pay for. Comparatively, products that users only use occasionally are much harder to build differential brand power.

One important note is that branding tends to work better than in consumer than b2b where companies don’t want to be beholden to one supplier.6 In the current AI landscape, OpenAI has a dominant lead in consumer adoption and Anthropic is barely a blip, yet the two are neck-and-neck in enterprise.

Where B2B brand can make a difference in the sense of “trusted vendor,” “you won’t get fired for buying it,” etc. that we will talk about in the next section on switching costs. It’s less about habitual purchasing and more about perceived stability. Another area where it can matter is in developer-centric or open-source startups where community is a big source of long-term brand advantage.

Switching Costs

This is one of the most powerful sources of competitive advantage, if one that Silicon Valley companies are often reluctant to claim as its own. The ethos and lore of Silicon Valley is “build great products people love” not “be so entrenched in a company that they can’t rip you out even if they hate you.” Yet, some of the most profitable and durable companies in software history are exactly the latter: SAP, Salesforce, Oracle, even Microsoft7 to some extent.

Being the system-of-record, bundling more and more products, operating in areas of low “category velocity” are great ways to make switching costs high. Distribution can be a moat in this sense. One of the biggest questions for foundation model providers is that switching between them currently only requires changing an API call. Ecosystem lock-in through other products, workflows, etc. is probably a necessary next step to try to establish a clear lead. Salesforce is one of the best modern examples of this, with an entire product suite and industry built around their company.

“No one ever got fired for buying IBM” is the mantra of a high switching costs company. If a company can establish itself as the de facto standard and only safe choice for buyers, it’s very, very hard to dislodge even if someone builds a superior product.

Let’s move to the last section for this piece which is economies of scale. As we’ll see more in part II, this is particularly powerful when interwoven with advantages in supply or demand.

Economies of Scale

The crucial factor for economies of scale is your share of the relevant market, not just how big you are in absolute terms. This is downstream of the Peter Thiel insight that great companies are monopolies in their market and the early market is often smaller or more “local” (in product space or geography) than people expect. Being dominant in a niche helps create economies of scale that you can extend at the outer edge.

Economies of scale typically arise in contexts with high fixed costs and constant or only slightly rising variable costs (famously, most software companies.) Spreading those fixed costs over more units lowers average cost per unit, making it possible to underprice competitors or sustain higher profitability at a given price. Netflix is one of the best examples with their “Originals” content: amortizing these fixed costs out over more subscribers than any of their competitors was an advantage that made it nearly impossible for all the would-be streaming competitors to compete economically with them. Each company could spend the same % of their total revenue on content, marketing, etc. but Netflix’s advantage in scale made it made it a losing battle.

NVIDIA in chip design is another example. NVIDIA’s massive scale advantage versus competitors gives it license to spend the same % of total revenue in R&D, dwarfing its competitors in spend, while spreading it out over a larger customer base. As long as they can match competitors’ offerings, they will not cede market share. In another era, this was the long-running story between Intel and AMD where AMD continually lagged as the also-ran. However, as that story also shows, these scale advantages need to be defended vs upstarts or shifting technology trends. NVIDIA cannot be lazy with its lead, but it has significant forces at their back in prospective battles.

Network effects are a type of scale advantage, where scale increases the value to customers not just lowers costs. In network-effect businesses like social networks or marketplaces, early scale leadership can quickly turn into a quasi-monopoly. However, this advantage is usually only with respect to direct competition: orthogonal competitors may be able to compete through a different value proposition (eg: Tik Tok vs Facebook/Snap).

A subtle nuance for founders is that a fast-growing market can lower the advantage of scale. Large, fast-growing markets lower the barriers to entry for competitors and the importance of fixed costs as a percentage of total costs declines, lowering any scale advantage. Until the market matures, it’s often hard to establish a clear dominant scale advantage: you’re one of many upstarts competing along the axes of operational efficiency, customer preference, etc.

Going back to the code-gen battles, the market is growing so fast and it’s so early that any lead in data or users that Cursor or Codeium has right now versus others is not a genuine scale advantage as other companies are also well-funded and can grow quickly. Customer captivity (demand advantage) is a possibility and probably the core of what companies should focus on, finding ways to build stickier feature sets, becoming more entrenched in workflows, building an ecosystem, etc. This is where Cursor currently has the advantage versus its competitors. If users build their development workflows around it, it will become harder and harder to switch over time.

Despite being nearly impossible to have a true moat in the beginning, startup founders should think directionally about where they can build competitive advantage over time.

Three practical takeaways for founders:

Accept that early-stage moats rarely exist. You need speed, focus, and to find product-market fit.

Some of the advantages you may have in people or technology are probably less defensible over time than you may believe. Think long-term about where structural moats can be built.

Be aware that your future moat might come from scale or from user entrenchment: build features or products that can enhance or take advantage of that.

Barring some sort of proprietary supply advantage through a defendable patent or singular founder/team, the strongest and most durable advantages in business come from a combination of scale with customer captivity.

Part II will explore three competitive advantage models that sit at this intersection: Aggregators, Scale Economies Shared, and Ecosystem Entrenchment. We’ll particularly focus on thinking about potential future advantages in the rapidly evolving world of AI companies.

Let me know if you have any thoughts, questions, or pushback to some of the frameworks discussed here. Moats are somewhat overrated in early startup discussion but important to think about as you build your business. Feel free to reach out to discuss at pratyush [at] susaventures [dot] com.

If you’re building a network effect business, it’s important to move quickly to get the network effect going as quickly as possible. As we’ll see later in the Scale section, being early does matter in these markets.

If this phrase is confusing, wait as we’ll dive deep into this one. It’s one of the most powerful sources of competitive advantage in business, but very hard to get right. Thank you Nick Sleep for the framework.

A quick note is one of my favorite powers from Helmer’s book (counterpositioning) isn’t listed here. The main reason is that counterpositioning tends to be a competitive advantage in the early days versus incumbents, but doesn’t help versus other startups pursuing the same model. I also think this competitive advantage tends to be more time-bound than the others listed here: it’s about a moment in time business model innovation versus one that’s a source of power throughout a company’s history.

Pun intended, post-DeepSeek.

Greenwald.

High switching costs are the only way they end up stuck with one supplier.

Despite being obviously superior products, the entire challenger ecosystem stack of Slack, Airtable, Notion, etc. has struggled to get a meaningful foothold in enterprise largely due to the powerful entrenchment and bundling power of Microsoft within those companies. It’s early but despite building a truly great product, one suspects Linear may encounter the same problem as it takes on Atlassian in larger accounts. A corollary to this entrenchment advantage is what Miles Grimshaw of Thrive called the “Workday transition” in reference to Lattice, a challenger HR tech platform he invested in. At some point, companies would inevitably hit a certain scale where they would graduate from Lattice to Workday: a CHRO or C-suite executive would come in and say it’s time to move to the more enterprise-y platform. The companies like Workday who have earned the right to be the recipients of the graduation have a real competitive advantage that’s hard to overcome.